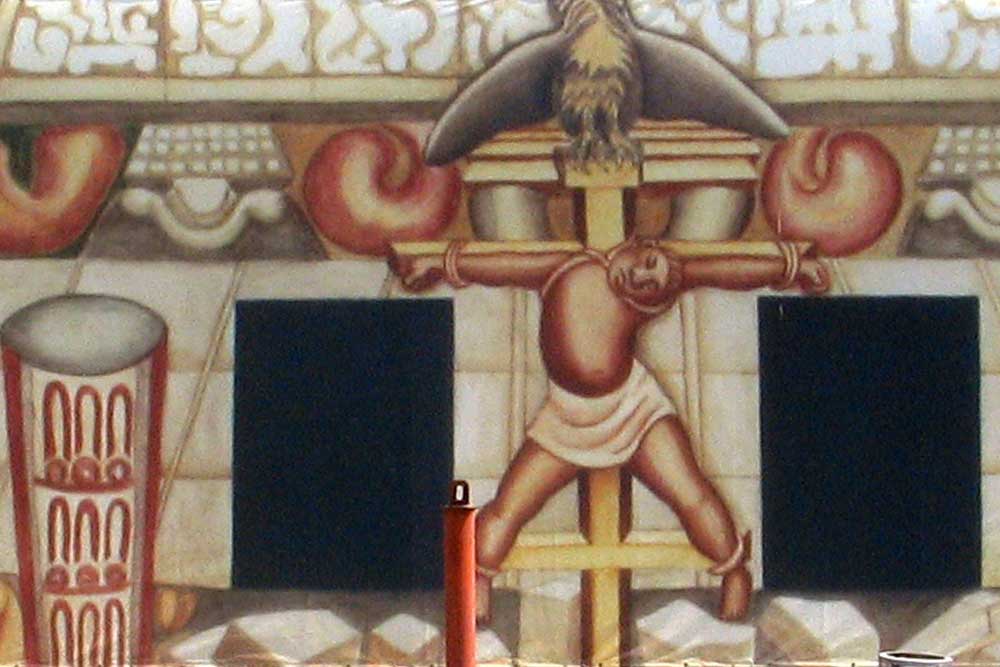

Detail from “América Tropical: Oprimida y Destrozada por los Imperialismos,” or “Tropical America: Oppressed and Destroyed by Imperialism,” in Los Angeles, California. The 98-foot-wide painting by Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros was painted over—literally whitewashed—soon after its unveiling in 1932. Restored by the Getty Conservation Institute, it has now returned to public view. Courtesy of The City Project/Flickr.

Los Angeles is just the second U.S. city to host the Summit of the Americas, which brings together political leaders, civil society organizations, and business executives from North, South, and Central America and the Caribbean to promote inter-hemispheric cooperation, economic growth, and regional security.

The very first summit in 1994 was held in Miami, often considered the hub of Latin America in the U.S. But this time around the Biden administration gave Los Angeles the nod, pointing to its “deep and robust ties throughout our hemisphere.”

This relationship is over a century in the making: Los Angeles owes its status as the second-largest city in the U.S. today to the wealth and capital that crossed over the border throughout the last 130 years.

This is a history deeply rooted in American empire. Rather than pursuing formal territorial control and annexation, American government and business leaders, including those in Los Angeles, advocated for economic domination in regions such as Latin America and the construction of an “informal” commercial empire beginning in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

L.A. boosters and investors, in turn, set about establishing a borderlands economy that reached deep into Mexico and beyond to make their city boom. They created a built environment to facilitate this growth: In the 1920s, members of the Los Angeles-based Automobile Club of Southern California, the nation’s leading motoring association, for instance, initiated construction of the International Pacific Highway, a 12,000-mile road which, in California, overlay the Pacific Coast Highway. When complete, the highway—which began in Anchorage, Alaska, and headed south along the Pacific Ocean—linked every country along the west coasts of North, Central, and South America. The Los Angeles businessmen and Mexican state governors who championed the project believed it would increase the movement of tourists and trade goods within the Americas, with particular benefits for L.A. And, true to form, when the road was completed in 1957, it traversed 13 nations and epitomized a new type of “informal” commercial American empire in Latin America—one that promoted free-market capitalism and globalization.

Over the decades, trade and commercial publications highlighted and reflected Los Angeles’ growing position as a center of U.S. trade and diplomatic relations with Latin America. Business and civic leaders launched Pan Pacific Progress in Los Angeles in 1926 to track trade between Los Angeles, the Western Hemisphere, and the Pacific world. Regular columns in the magazine monitored metrics such as annual Pacific ports tonnage to gauge the number of goods moving between Latin American and U.S. Pacific ports. Others outlined trade and commercial possibilities with Latin America, ranging from the export of citrus to mining for zinc to building shipping infrastructure; and introduced American readers to presidents of Latin American republics including Mexico, El Salvador, Ecuador, and Brazil.

Anglo Angelenos were committed to furthering these hemispheric relationships. David Hamburger, a contributor to Pan Pacific Progress and successful department store proprietor who’d lived in Los Angeles for nearly half a century, reflected in 1929 that Los Angeles went “from a desert town to a metropolis that is bound to become the largest and greatest city in the world, economically and geographically.” In the piece, he advised American readers to take their capital to South America and approach business partners there with a cooperative spirit. “If we, with our experience, will lend our advice and assistance to our [South American] neighbors there is no limit to the profit to be derived,” he wrote, promising a “gigantic success will be assured.”

In the 20th century, Los Angeles boosters further tied their city’s fate to the exploitation of natural resources in Latin America, particularly Mexico, believing they needed to reach beyond the U.S. to grow. The city’s Chamber of Commerce organized investment excursions across the border. Oilmen such as Edward Doheny drilled wells in Mexico’s petroleum regions; the interlocked Chandler and Otis families, owners of the Los Angeles Times and successful real estate developers and corporate ranchers, developed a million-acre cotton and cattle ranch in northern Mexico. These ventures proved wildly profitable. Mexican resources helped transform the small town of Los Angeles into a large, successful, and prosperous city.

But this prosperity and success has not flowed both ways. While facilitating trade and investment, 19th- and early 20th-century Los Angeles boosters carefully controlled labor flows for the benefit of U.S. agricultural and industrial employers. Fruit growers with headquarters in Los Angeles, for example, actively recruited agricultural workers from Mexico whom they identified as an inexpensive, “compliant,” and reliable labor source to work in California’s Imperial Valley and citrus belt. As noncitizens, these workers had little recourse to challenge or improve poor wages and harsh working conditions.

Beginning in the 1960s and accelerating through the ‘70s and ‘80s, federal economic policies have deepened this inequality. The U.S. government’s push to lift regulations, free up trade, open markets, and promote private investment in Latin America led to collapses in industries such as agriculture, forcing millions of workers to flee Mexico and other countries. It is America’s “new imperialism”—nothing short of the “third conquest of Latin America,” as historian Greg Grandin observes in Empire’s Workshop, following Spanish colonization and American corporate and military interventions in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

This forced mass migration from Latin America has continued to benefit Los Angeles, providing an influx of creative and economic talent that has remade and revitalized parts of the city, creating community and businesses, and invigorating neighborhoods such as MacArthur Park—once abandoned due to white flight, and now a residential and commercial center for Central American immigrants. Meanwhile, Latin Americans seeking refuge in the United States continuously find their economic opportunities limited to the agricultural and service sectors and the underground economy, and face below-minimum wage pay, dangerous working conditions, and scarce enforcement of labor laws. Complicating matters further is the shadow of the Immigration Act of 1965, which placed limits on immigration from the Western Hemisphere just as U.S. dependence on Latin American labor intensified. This curtailment of legal entry led to mass undocumented immigration, compounding workers’ vulnerability.

At the summit in Los Angeles, we can expect leaders from across the hemisphere to lay out a strategy to maintain and stimulate U.S.-Latin American trade, and to promote regional “economic growth and prosperity based on [a] shared respect for democracy, fundamental freedoms, the dignity of labor, and free enterprise,” as the State Department puts it. But any honest movement in this direction must reckon with the U.S.’s long history of disruptive economic and political policies in Latin America, as well as its restrictive immigration policies and simultaneous reliance on immigrant labor. Because Latin America made Los Angeles—and Los Angeles, through the ties of commerce and migration, is part of Latin America.

Send A Letter To the Editors