Christopher Endy argues for more access to international travel, as tourism has, historically, “instilled a sense of which foreign places matter to the United States.” Courtesy of AP Images.

As the United States sends stockpiles of weapons to Ukraine, another transatlantic mobilization is underway. Freed from two years of COVID restrictions and testing requirements, Americans are once again traveling in large numbers. Market observers have predicted a six-fold increase in American tourism to Europe compared to summer 2021.

If you’re wondering what shipments of weapons and planeloads of tourists have in common, the answer is: quite a bit. Tourism has long had a way of getting mixed up in international politics.

It is easy to overlook tourism’s political importance. After all, most Americans journey abroad seeking fun or exposure to a country’s history, food, and art. The goal is usually to escape news headlines, not study them in detail.

Tourism is also easy to dismiss as a superficial activity involving pre-packaged, staged encounters. The word “tourist” began in the 18th century as a neutral synonym for “traveler,” but, as the literary historian James Buzard has shown, cultural sophisticates soon turned the word into an insult. Starting in the mid-19th century, self-declared travelers sought to bolster their own cultural status by ridiculing tourists as thoughtless sheep. The most famous American version of this anti-tourist position came from popular historian Daniel J. Boorstin. In his 1962 book, The Image, Boorstin lamented how the rise of convenient transportation across the oceans rendered travel experiences “diluted, contrived, prefabricated.” According to Boorstin, a genuine traveler takes risks and interacts with locals, while tourists merely follow someone else’s script.

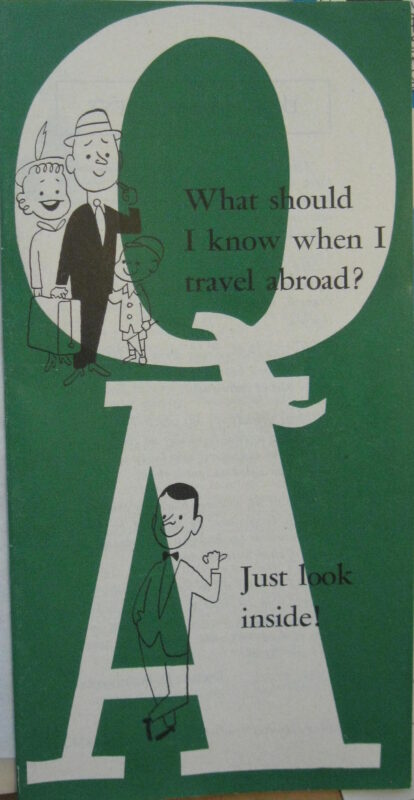

The U.S. Information Agency (USIA) saturated travel agencies and airlines with this booklet. Photo taken by author. Courtesy of U.S. National Archives in College Park, Maryland.

It’s a mistake to stereotype tourists in this way. The historical record shows that tourists are pretty good at thinking for themselves. My research uncovered many examples. Here is one: Exactly 70 years ago, as the Korean War raged and the Iron Curtain divided Europe, the U.S. government decided to coach American tourists on how to prepare for encounters with communists and their supporters. It was the height of McCarthyism in the United States, but grassroots communist movements thrived in Western Europe. In fact, many of the waiters and chambermaids serving Americans in France’s luxury restaurants and hotels belonged to communist labor unions. So, in 1952, the U.S. Information Agency (USIA), working with civic organizations, saturated travel agencies and airlines with a booklet, “What Should I Know When I Travel Abroad?” If Americans met a Western European who wanted to negotiate with Moscow, the booklet suggested that Americans respond politely but firmly: “It seems to us that in the fight between what is right and what is wrong there just isn’t room for neutralism.”

Actual tourists, however, didn’t follow the script. The USIA interviewed several hundred Americans in their homes after their 1952 trips. Most appreciated the booklet, and a surprising share—71 percent—claimed they read it cover to cover. Still, the government’s diplomatic experts found troubling signs. When it came to explaining something as basic as “America’s concern with Communism,” the report found Americans “ill-equipped.” Alarmingly, the USIA learned that Americans took “a less-determined stand” on European neutralism than their government’s recommendation. Fully one-third said that their travels helped them understand European desires for negotiating with the Soviets. One tourist admitted to the USIA, “I couldn’t say anything. I could only sympathize.”

Indeed, international travel can help build solidarity with other countries. As the USIA learned, tourists aren’t so good at following specific political talking points, but tourism has, historically, instilled a sense of which foreign places matter to the United States. Why is the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) so popular in the United States today? One reason is that Americans have for so long visited Europe in search of cultural treasures—making those nations feel like part of a shared community. When World War I erupted, wealthy Americans who had traveled to Europe before the war became the most vocal advocates for U.S. entry into the conflict, citing their tourist memories, especially of embattled France. One influential magazine in 1917 offered a lavish 16-page photograph spread showcasing French tourist sites “to help perpetuate … the bond of romantic affection” linking America to France. During the next war, while Adolf Hitler posed for snapshots by the Eiffel Tower, best-selling books like The Last Time I Saw Paris built U.S. commitment for fighting Germany with travel writing that described France as part of Americans’ own heritage.

What does the political nature of tourism mean for today? For starters, Americans with the ability to travel abroad should think more deliberately about combining politics with pleasure when choosing their destinations. NATO’s self-defense clause obliges the United States to risk World War III for the safety of countries like Estonia. My guess is that few Americans could locate Estonia on a map. Next summer, why not skip Paris or Rome and visit Estonia’s charming capital of Tallinn? Learning about newer NATO members will help Americans develop more informed opinions on the risks and rewards of their nation’s foreign commitments.

Government officials themselves should give more attention to tourism’s ability to sustain those bonds of affection. The American Chamber of Commerce in Taiwan has called on Taiwan’s government to welcome more foreign tourists as a matter of “national security.” The U.S. government would be wise to give tourism similar attention. When it comes to popular culture, politicians usually fixate on what’s novel. That’s why, after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Biden White House organized a briefing for TikTok influencers. As far as I can tell, the Biden White House has not reached out to the travel industry or the millions of tourists heading abroad this summer. The president cannot make tourists support his policies, but he can encourage them to listen to and learn from our allies while abroad.

Washington can also help make foreign travel accessible for more Americans. In an age of polarization, international travel remains refreshingly bipartisan. According to a 2021 survey, 41 percent of Democrats and 38 percent of Republicans reported having a valid passport. But that percentage drops to 21 percent of Americans with annual incomes under $50,000. In 1949, the widely respected journalist Norman Cousins called for government subsidies to help poorer Americans travel abroad. Washington could follow that advice today by waiving passport fees and bolstering exchange programs for low-income Americans—not as a form of charity but as way to broaden Americans’ engagement with foreign policy.

Overseas vacations have always involved politics alongside leisure and escapism. Your next vacation by itself will not change the world, but it will become part of the next chapter in international history.

Send A Letter To the Editors