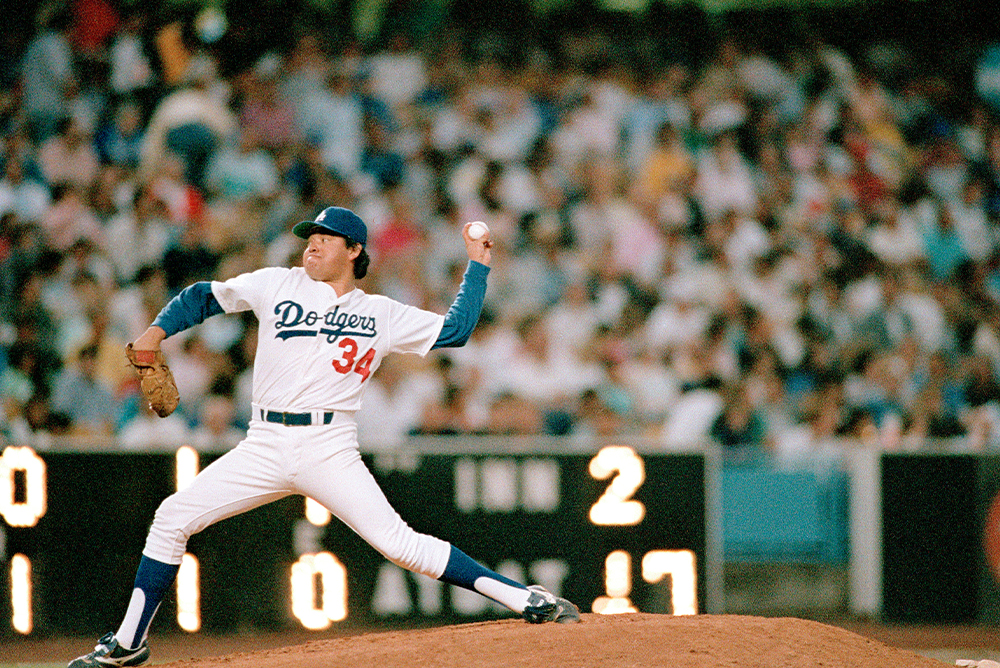

USC professor Natalia Molina reflects on growing up near Dodger Stadium and grappling with its dark history of displacing Mexican and Mexican American families. But she also notes that people like Fernando Valenzuela, pictured above, have served as “a bridge and ambassador between the Latinx community and the Dodgers.” Courtesy of AP Newsroom.

As a kid growing up in Echo Park in the 1970s, I would walk to Dodger Stadium with my brother or kids in the neighborhood. For three dollars, we could purchase an upper deck seat and for an additional three dollars, we could get a Coke and hot dog. We would arrive before the game and have the players sign our balls, which I still have today. We often ran into food service workers we knew: Some had been employed at my grandmother’s restaurant, the Nayarit, which she opened on Sunset Boulevard in 1951, and some at Barragan’s, another neighborhood anchor opened by a former Nayarit employee, Ramon Barragan.

As I write in my recent book, A Place at the Nayarit, these workers took second jobs in food service at Dodger Stadium, staffing the approximately 81 home games of the six-month season. Some worked the fast food stands—they’d often sneak my brother and me free snacks. Others were in more exclusive areas they would never have had access to without their jobs: the private members-only Stadium Club, which housed its own bar and restaurant, and the Club level, which housed the press box and where one was likely to bump into former Dodgers and celebrities.

Once workers had gained access to these exclusive spaces, they extended the entrée to many of their friends, giving them complimentary tickets or letting a friend slip in the door when the manager was on a break. My brother, David Porras, remembered going to the Stadium Club with friends as a young boy in the 1970s, thanks to a Nayarit connection. He drank complimentary Shirley Temples packed with extra maraschino cherries and marveled at the 9-foot 3-inch taxidermied polar bear, which former Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley had killed on a hunting trip in northern Norway and which towered over the room on a specially built pedestal. (David still knows who can get us into the Stadium Club without passes.) Access to these spaces gave ethnic Mexican workers and their friends real and imaginative mobility, and at the center of it all, was our love for Los Doyers.

But loving the Dodgers can also be complicated if you’re Latinx.

Dodger Stadium sits where there was once a close-knit residential community called Chavez Ravine. Working class and racially mixed, but predominantly Mexican and Mexican American, the neighborhood was located in Elysian Park just over the eastern border of Echo Park. Broadcasters calling games at Dodger Stadium still use the name to harken back to these days, but they never mention the site’s dark history (a history that begins even before Chavez Ravine existed: L.A. is on Tongva-Gabrielino land).

Beginning in 1951, the city used eminent domain to seize land in Chavez Ravine for a public housing project. The city’s urban renewal authority forced residents to vacate their homes and abandon the neighborhood. They told homeowners that they had bought them out at market rate, but few could find equivalent properties for the low prices they had been paid. Renters were promised that they would be given first rights to the public housing that would be built over their razed community.

Yet after the residents were displaced, the project languished. As the Cold War intensified, public housing was deemed too much of a “socialist experiment” to build. In 1959, to bring Major League Baseball to Los Angeles, the city sold the land to O’Malley, owner of what was then the Brooklyn Dodgers, at a fraction of its worth. Ground broke for the construction of Dodger Stadium that year. This led to the most well-known of the Chavez Ravine evictions: that of the Arechiga family, which included an adult daughter, Aurora Vargas, being forcibly carried away by deputies. The emotional scene was followed by the entrance of bulldozers that razed their home.

When I was growing up in Echo Park, I didn’t know this history. I don’t think most people know it today. I learned it once I got to UCLA, in a geography class with Gerry Hale. He was not even a Chicano, but a white man who engaged in a one-man boycott of Dodger Stadium, having made a personal commitment to never go to ballgames because of what had happened on the land on which Dodger Stadium sits.

If that’s the only part of the history you know, and especially if you’re Latinx, you might hate the Dodgers. But in fact, one-in-two Dodger fans at any given game is Latinx. After learning about Chavez Ravine, I remember feeling conflicted. Here was yet another chapter in the history of Latinx disenfranchisement, but I also knew how connected I felt to the team.

Some people trace the turning point of the Latinx community to Fernando Valenzuela and his magic left arm that led the Dodgers to so many victories. But my love for the Dodgers, and that of the people I grew up with, preceded Valenzuela (though don’t get me wrong, I had a button with his picture on it that I wore to every game in grade school). Throughout my formative years of fandom, I remember admiring Pedro Guerrero, Manny Mota, Pedro and Ramón Martínez, Ismael Valdéz, Raúl Mondesí, and Adrián Beltré. Plus, we had Jaime Jarrín, Hall of Fame broadcast announcer for the Dodgers, who called the games for us in Spanish, serving as a bridge and ambassador between the Latinx community and the Dodgers.

Señor Jarrín will retire this year. I was honored to interview him recently for my book about Nayarit restaurant. The Nayarit was a place where immigrants such as Señor Jarrín knew they could speak Spanish, bump into friends, and feel at home. Remember, we’re talking about 1950s, ’60s segregated L.A., right on the heels of Mendez v. Westminster. Edward Roybal had only recently been elected as city councilman for East Los Angeles—the first Latino elected in L.A. since the U.S. takeover in 1848. When Señor Jarrín traveled to other ballparks to announce Dodgers away games, they would stick him wherever—sometimes next to a pole, making it difficult to see the game and make the calls. He knew what it took to make space for others. Señor Jarrín was a “place-maker” at Dodger Stadium, letting Latinx L.A. know that this was their team, helping people feel at home in the stadium.

Nowhere else in L.A. do I feel more like an Angeleno, Chicana, or part of the collective human experience than at Dodger Stadium. It’s love for Los Doyers, but also my fellow fans. During a postseason game last year, my seatmate was an L.A.-born Chicano living in the Bay, who drove down to be there. His cousins joined him, just as they had been going together as they were kids, similar to the way my family descends together upon Dodger stadium with the same feel, love, and spirit as if we were going to a family carne asasda. His family and mine linked arms as the mariachi—playing from the bleachers, surrounded by some of the most loyal Dodgers fans—started playing “Volver, Volver,” and belted out the unofficial Mexican anthem.

Places are made not just by the people who tear down neighborhoods to build stadiums but the people who work in and around the stadium: who play baseball, who come to them for a sense of community, and who follow what goes on from their radios. History is complicated that way—a rich palimpsest with layers of joy, layers of sorrow, layers of connection, layers of estrangement.

Send A Letter To the Editors