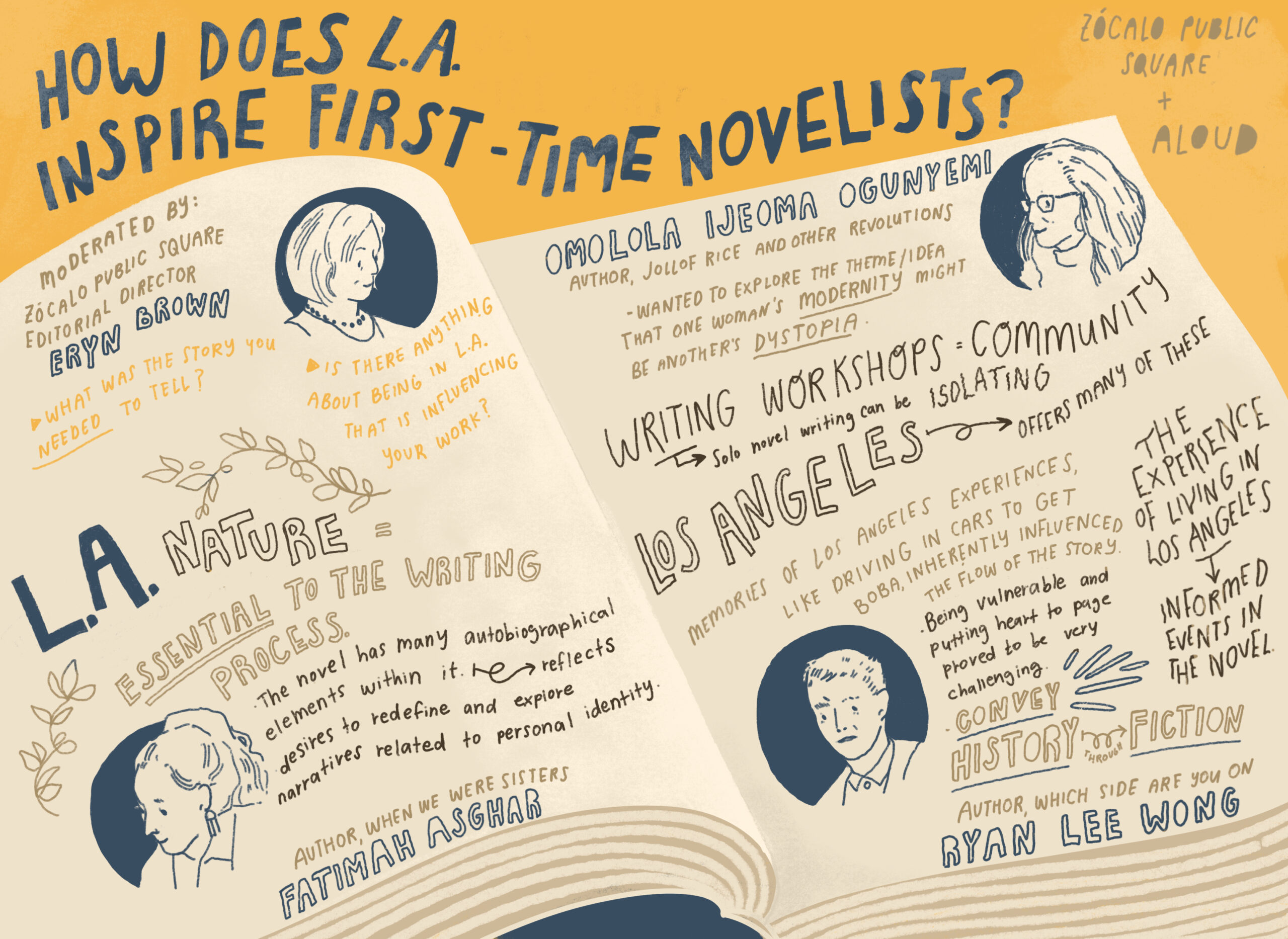

From left to right: Eryn Brown, Fatimah Asghar, Omolola Ijeoma Ogunyemi, and Ryan Lee Wong.

It is said that Los Angeles lacks a literary pulse—that the flash and glam of Tinseltown overpowers the cultural terrain. But writers here deftly channel this city’s rhythms, spinning fictions of folly and fortune that unfold under its roofs and along its streets. Last week, Zócalo, together with the Library Foundation’s ALOUD, honored L.A.’s literary side in a lively discussion with Fatimah Asghar, Omolola Ijeoma Ogunyemi, and Ryan Lee Wong, three first-time novelists writing in or about the city.

The event, “How Does L.A. Inspire First-Time Novelists?,” opened as each writer narrated an excerpt from their new work: Asghar, reading from When We Were Sisters, painted a scene of a sisterhood of orphans enduring life with a neglectful caregiver; Ogunyemi, reading from Jollof Rice and other Revolutions, described a student uprising against a domineering boarding school principal in Fiditi, Nigeria who tries to mollify her charges with the promise of jollof rice; and Ryan Lee Wong, reading from Which Side Are You On, offered a protagonist’s soliloquy that waxed pedantic over racial capitalism.

Eryn Brown, Zócalo’s editorial director, moderated the event. She began by asking all three panelists, “Why write a novel?”

Asghar, an accomplished poet who is also an educator and screenplay writer (most recently for Disney+’s Ms. Marvel), said that the organic unraveling of their story pushed up against the poetic form’s limitations. “Poetry is a home for me,” they said. “But there was something about the narrative that was coming to me that was beyond poetry. A lot of the characters and themes couldn’t be contained to one poem.”

For Ogunyemi, hearing of a great aunt’s marriage to a woman in turn of the century Nigeria spurred her to think deeply about her family’s history. She always knew that her book would be an interlocking set of stories, and that she wanted to explore different themes in women’s lives across generations to show the multiplicity contained therein: “Depending on where you’re coming from in history, one woman’s modernity is another woman’s dystopia.”

Wong wanted to write about the L.A. uprising of 1992, when the city erupted in turmoil after a jury acquitted the police who beat Black motorist Rodney King. Wong, who grew up in L.A., was only four years old at the time, but his mother, who was seated front row of the audience, had worked with the Black–Korean Alliance in the 1980s. “That whole history has always haunted me, cast a shadow over the city, over my life,” he said.

His novel draws on this family history and his own recent experiences as a young activist in the wake of a Chinese American police officer shooting and killing a Black man in a public housing stairwell in Brooklyn. Still, there is a “screen” between the characters and their real-life counterparts, which allowed him to face the hard truths of this history, Wong said. “I knew these histories were so painful that only fiction had the capacity, emotionally, to hold them. Fiction is still one of our best vehicles for showing a character’s internal transformation.” By relating these two moments of activism—his mother’s and his own—he also set out to tell a story of intergenerational trauma, and pasts that do not remain past.

What about when these authors actually sat down and started writing their novels—what did they have to learn, and what caught them off guard?

Writing a novel was isolating, all said. Asghar, who came up through the poetry community performing spoken word—a “very oratory experience”—found novel-writing “incredibly not community-oriented.” They started writing their novel in 2018, completing it this year. “It was one of the most isolated and meditative processes,” they said. “It was a lot of learning how to listen and trust yourself and trust your intuition.” The editing process, too, differed from poetry. With a poem, they would “edit out loud” based on audience reactions. But if they changed anything about a character or plot point in the novel it rippled throughout the book, with consequences outside a particular scene.

Wong agreed. No stranger to isolation, having spent two years in a Buddhist temple, he described writing his novel as a quiet process, but also one that could be grueling: “You have to let your characters suffer. You have to let your characters be painfully wrong sometimes.”

Ogunyemi, too, spoke of writing alone. It took her 15 years to finish Jollof Rice; she was also busy with a career in bioinformatic research. Ogunyemi said the single-handedness of writing a novel was a departure for her: “Scientific writing is often not a solo effort, you have lots of papers with lots of co-authors.” But Ogunyemi found community in writing workshops in L.A., where feedback changed the novel’s focus.

What else about L.A., and about L.A.-ness, Brown asked: Is there something about being here that creates interesting work like this?

For Asghar, it was the city’s natural landscape. “L.A. was one of the first places I’ve lived that opened nature to me. I grew up thinking nature is for white people, I had no conception of nature as something as a home for me,” they said. Going to the ocean and being able to go for hikes helped them as they wrote, they said.

Wong drew upon L.A.’s built environment. Growing up, his notion of the city included the narrative that nothing ever happened there, “that we just drive around and get boba in strip malls.” Only by leaving L.A. could he realize that these kinds of everyday moments were also legitimate experiences, that “in between moments in the car, in strip malls, that’s where life happens.”

As the hour’s end neared, online questions flooded in and in-person audience members lined up to pose their questions. One attendee asked, “What of your own personal background do you hope shines through that is not typical of a Western narrative?”

Violence as entertainment, Wong said, is a Western notion he tried to reject. Ogunyemi employed a non-Western setting, with much of her novel taking place in Nigeria. Asghar’s novel counters the “resilience narrative” that’s so prevalent in the West. Characters don’t necessarily rise above; rather, the novel grapples with “what actually happens when people are sitting with the trauma they’ve experienced.”

At the reception that followed, all three novelists signed copies of their books for enthusiastic audience members. During the program, Asghar had spoken about this very act. Once you release a novel into the world, they said, “once the language hit[s] the air,” something that was “so deeply yours” becomes everyone else’s.

Send A Letter To the Editors