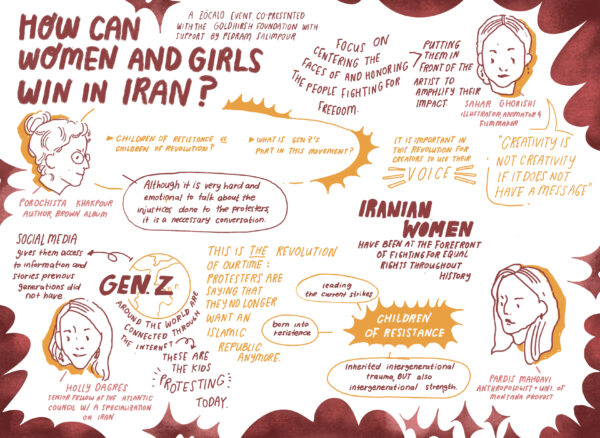

From left to right: Porochista Khakpour, Holly Dagres, Sahar Ghorishi, and Pardis Mahdavi.

Last night, a quartet of Iranian women took the Zócalo stage to discuss the uprising in Iran, where a general strike has entered its third day and protests persist after nearly three months. Co-presented with the Goldhirsh Foundation and with generous support from Pedram Salimpour, “How Can Women and Girls Win in Iran?” brought Atlantic Council senior fellow Holly Dagres, artist Sahar Ghorishi, and anthropologist Pardis Mahdavi to ASU California Center in downtown Los Angeles. The event was moderated by author Porochista Khakpour.

Khakpour jumped in, asking Dagres to share some words about video compilations she put together of content Iranians had posted online. One featured 16-year-old vlogger Sarina Esmailzadeh living her life as a teenager—cooking and singing along to pop songs—and calling for more freedom. “We’ve also seen those in Los Angeles enjoying life to the fullest,” she says in Farsi in one clip, alluding to the way social media has connected her generation. “Freedom is loading.” Esmailzadeh was beaten to death by police forces while protesting in September.

“Social media is the only way for Iranians to be heard by the world,” Dagres said. Drawing on her research, she discussed how social media is used not only to document human rights abuses, but also as an accountability tool, to mock officials through satire, and draw attention to issues through hashtags. And because Iranians must make deliberate use of tech tools such as VPNs to circumvent the state’s control over the internet, Dagres explained that “what you see coming online, it’s because they want their voices to be heard.”

The current movement is a “social media uprising,” Dagres said, sparked by hashtags and viral images of a comatose Jîna Mahsa Amini, the 22-year-old Kurdish Iranian woman who died in state custody after eyewitnesses reported seeing her beaten by the Guidance Patrol also known as the “morality police.” That this movement is populated by the younger, born-digital Generation Z is of import, Dagres said. “They’re not going to settle and accept the living standards. They don’t want this for their future.”

The current movement is a multigenerational one, too, Mahdavi pointed out. While before there were the “children of the revolution,” who came of age after the 1979 Islamic Revolution and protested during 2009’s Green Movement, now there are the “children of the resistance.” Mahdavi noted that she sees schoolkids her daughter’s age bravely singing anthems, tearing pages out of textbooks, and saying “enough is enough”; they are supported by older generations. “They’ve inherited our intergenerational trauma and our intergenerational strength.”

In addition to the multigenerational element of the current uprising, it is important to center minorities “at the forefront” in the struggle, Ghorishi said. Citing Iran’s great diversity, she uses her art as revolution, and to bring attention to minoritized voices—of Kurds, LGBTQI+ people, and people with disabilities. “It is these people who are fighting,” she said. Khakpour agreed, “There’s a really inspiring language of inclusivity now that I feel personally has been missing a lot in different eras.”

All four panelists were in consensus that throughout the eras and various movements in Iran’s history, women led the charge. Mahdavi, partly responding to Dagres’ point about new media, noted that during the Islamic Revolution women smuggled in cassette tape recordings from an exiled Khomeini to spread the gospel of the revolution. Women, too, were at the forefront of the constitutional revolution in the first decade of the 20th century.

As the conversation came to a close, questions from both the online chat and in-person audience prompted the panelists to draw parallels to activism here in the U.S. Mahdavi urged people to think about the transnational context and how the seeds of social movements inform one another like “roots and branches strengthening each other.” She has heard from Iranians that BLM and the #MeToo movements, for example, were formative in helping find their voice and courage. Viral images of police brutality are another parallel. Mahdavi, too, brought up the notion of justice feminism—a topic she discussed as part of a 2021 Zócalo event on transnational women’s movements—which brings forward the idea of feminism’s intersectional roots and offers a means to share strategies across movements that can reverberate across the globe.

A final question from an in-person audience member prodded the panel to imagine what would happen if there were regime change in Iran from these protests: Then what? Who will our leaders be? Dagres took this one, noting Iran’s highly educated population and their experience with democratic processes like voting. “Don’t underestimate the people of Iran,” she said, “Just because [the movement] is leaderless doesn’t mean it’s meaningless.”

Just before the panelists left the stage, Ghorishi shared a somber and sobering slideshow that she and some collaborators had made to highlight the faces of those who had been killed during the uprising thus far. The faces and names of these mostly young protesters moved across the screen in memoriam. And throughout the evening, shows of solidarity—from the panelists, from the online chat, during the reception, and on a small altar that Ghorishi assembled outside the room dedicated to political prisoners, “freedom fighters,” and the rallying cry of the movement: “Women, Life, Freedom.”

Send A Letter To the Editors