Photo by Neal Santos.

Raven Chacon has been making noise, literally and otherwise, since he was a youngster growing up in New Mexico. Fascinated by instruments of all kinds (those he’s bought and those he’s built), the 45-year-old Diné composer and artist has spent a lifetime studying the sounds things and people make, and creating experimental performances that build upon that noise, melodious and otherwise, to make listeners think about the places they inhabit: physical, spiritual, artistic, and intellectual.

Today, Chacon’s music is having a moment. In 2022, his composition for church organ and ensemble “Voiceless Mass”—a piece that “considers the futility of giving voice to the voiceless, when ceding space is never an option for those in power”—won a Pulitzer Prize. And in August 2023, the MacArthur Foundation awarded Chacon its prestigious “Genius” grant, lauding his “practice that cuts across the boundaries of visual art, performance, and music” to activate “spaces of performance where the histories of the lands the United States has encroached upon can be contemplated, questioned, and reimagined.”

On December 14, Zócalo and partners wasteLAnd, GRoW Annenberg, and ASU Gammage present “How Do We Hear America?,” an evening showcasing performances of two Chacon works: “American Ledger No. 1,” an ensemble piece performed beneath a giant, flag-inspired score that tells the creation story of the U.S.; and “Echo Contest,” a call-and-response duet that plays with notions of distance. The program will take place at the historic ASU California Center, in downtown Los Angeles. (Tickets are free. Sign up here.)

Zócalo’s editorial director Eryn Brown caught up with Chacon over Zoom to talk about the saxophone sitting on his couch, how Los Angeles influences his work, and what it means to be American.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you get into music in the first place?

When I was a little kid, I was just fascinated by it. I really wanted to play saxophone. I wanted to play electric guitar. I wanted to be in a band.

After my family moved from the reservation to Albuquerque, I was able to take piano lessons with a piano teacher. I can’t say I was a good pianist, but I learned to read music. I was really interested in that, and it was something I was good at.

Once I could see all the notes on the musical staff and then find them on the piano, it made a lot of sense, and I was able to understand how other instruments worked—the violin, the cello, the viola—their role, and their register, and where they fit into the greater family of instruments.

I started teaching myself how to play them. That continues today. I’m still trying to learn the saxophone. I bought one about 15 years ago, and it sits there on the couch.

Is saxophone particularly hard?

For me it is. As a young person, I tried to play clarinet just to be in the band, but my musicianship wasn’t good enough. And that’s OK. That got me interested in trying to make my own instruments—my own guitar, my own percussion.

I started making music using contact mics and guitar pickups. Back in the ’80s and ’90s, cassette tapes were ubiquitous, so I found ways of making sound and music with them: recording, re-recording, and splicing, using the pause and record button in a way that the cassette player became its own musical instrument.

You refer to a lot of your work as “noise music.” What does that mean?

That was the thing I was doing with the cassettes. If I were put on the spot to define it, maybe it’s prioritizing parameters of music other than fidelity—pitch, and melody, and rhythm—which can equate to distortion or dissonance.

The very technical, literal, and scientific definition of noise is that it’s every frequency at once. The static on the television set, for example. Using homemade instruments, and feedback, and overamplifying objects is a noise musician’s attempt to be everything at once.

One thing I like about noise music is that it plays with the idea of time. One of the identifiers of music throughout human history is that it has a pulse: You find the rhythm of your own body within music. That’s probably why all humans love it.

But noise music can stall time. You can enter the experience at any moment. Maybe you didn’t have to see the beginning, and you don’t have to see the end, and you just entered in the middle. And in that moment, you experienced everything you would need to know inside of that piece of music. To me, that’s wonderful.

Is “American Ledger No. 1” noise music?

When I wrote it, I was just thinking of it as a chamber music score. But since it is so open-ended, it can surely incorporate noise.

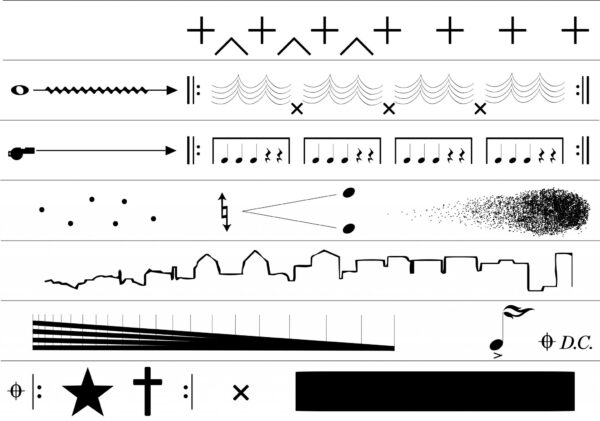

The “American Ledger” series is based on flags of places in the United States: No. 1 is a representation of the U.S. flag, No. 2 is the Oklahoma state flag, and No. 3 is the Illinois centennial flag. The scores themselves are displayed as objects during the performance—a flag that can be hung on a wall, or flown on a flagpole.

The flag is also the sole document that gets read during performance. The musicians all see the same score, audience, ensemble, and conductor. The abstracted shapes of the score provide a narrative, with specific musical prompts. For instance, you chop wood when you see an axe. You throw coins when you see a bunch of dots. You light a match when you see an eighth note that has a flame at the top.

These acts and gestures tell the creation story of the United States.

Does the piece change, depending on where you play it or where you hang the flag? Have you seen people interpret it differently in different locations?

It’s different every time. People start on a different pitch every time. And it doesn’t specify what instruments to bring. It just says sustaining instruments and percussive instruments, which might encompass every instrument that exists.

And things that aren’t even instruments too, right?

Yeah, like a bowed metal pipe or something. Or a toy. Well, I don’t want to put those ideas out there, because somebody will bring a kazoo or something.

But yes, as long as it’s sustaining or percussive, I’m very open to what somebody might bring to this, as long as they are trying to tell the very serious and violent history of the United States.

I’ve noticed that the more this has been performed, a regional sound emerges. The way a guitarist from Texas plays can be very different from a guitarist from California.

Speaking of place, I wanted to ask you about site-specificity, and its importance in your work. We’re presenting your music at the Herald Examiner Building in downtown L.A., where William Randolph Hearst ran his newspaper empire. The lobby where “Echo Contest” will be performed is this extremely ornate sort of temple to a man who was very powerful and very complex, in California and American history. And “American Ledger No. 1” is going to be displayed and performed in the room where his newspaper’s printing press used to be.

I didn’t know that. That’s really fascinating.

I wrote “American Ledger No. 3” as a dedication to Ida B. Wells and her writings documenting lynchings in the South. I was motivated by renewed awareness of police brutality during the pandemic. That score is in the form of a flag, as is the rest of the “American Ledger” series, but it is also in the form of a newspaper.

I’ve been thinking about the role of journalism in our country. It’s a freedom and privilege that we have access to information. And the responsibilities of sharing and documenting are a special freedom and power.

At the same time, the architecture of these spaces exalts figures like Hearst, and their wealth. We are invited to make music in them, but how can we also intervene? We work in these halls that are meant to celebrate a power, but we are also in a position to respond to it. It’s really fitting that “American Ledger No. 1” can exist in this space, and that we have an opportunity to have a conversation of dissonance within it.

I wanted to talk with you about L.A. You’ve lived here, right?

Yes, after I completed my studies at CalArts. For four or five years. I lived in the San Fernando Valley, and I lived in East Hollywood a bit.

Has the city influenced your work?

I don’t know what I’d be doing if I didn’t go to CalArts. I was already doing this kind of work, making noise and improvising, but I didn’t know that could be a career until I went to CalArts and got connected with that community.

There were very few experimental musicians in New Mexico. One reason I moved to L.A. was to seek people who were doing this kind of thing. I found them immediately, and it greatly influenced my work—just being amongst other musicians, playing with a lot of other musicians, seeing live music every night.

I have to mention Il Corral, run by my longtime collaborator Bob Bellerue, who lives in New York now. Bob also was going to CalArts. I used to help out at the venue, and I saw hundreds of concerts, just working the door. That was very formative, even though I was probably in my mid to late 20s. Just having that much access to local and touring musicians, coming through Los Angeles.

Is L.A. or New York the epicenter for experimental music today? Or both, in different ways?

New York definitely has its own community, and it’s more of a destination for any musician who’s touring internationally. Surely there’s a lot of activity here, and longstanding traditions of improvisation as well.

But there was a different kind of scene happening in the early 2000s around noise music in Los Angeles that was very energetic, very spontaneous, and very diverse. A lot of people of different ages, men and women, people of color, were making music. To me that was very exciting.

Will the MacArthur Fellowship allow you to do new things?

I should have more time to try other mediums. I’ve been working a lot with video over the past 15 years, both as a member of [art collective] Postcommodity, and in my solo practice. It’s something I want to explore further.

Another thing the fellowship will allow me to do is continue projects like Sicksicksick Distro, the record label I started in New Mexico. It was a DIY approach to releasing music, both my own and that of other Southwestern musicians. It was always self-funded, and I was always making the cassette tapes, making the artwork, going to the post office, and mailing these things out. That project had slowed down, and now I have the resources to start it up again.

There are new people all the time making new projects, new music. I’ve always tried to prioritize Indigenous artists from reservations. I need to catch up and see what they’re making.

Are the releases now online? Do they stream?

I leave the digital distribution part up to the artist. I’m more interested in making a physical product, whether that’s a vinyl release, a cassette release, maybe a zine.

You’re onto something with physicality and music. It’s the same thing with your scores. The visual existence of that score in the room is so impactful.

I think something that has gotten lost with not always having access to physical recordings is liner notes. Some insight into the lyrical content or other ideas that went into the music, who plays on the recording, where it was made, maybe other kinds of esoteric information like ramblings, or drawings. I think it is just as important as the music oftentimes. It tells you where the music is coming from. Not just geographically, but what person is making it. To me, that’s fascinating.

Zócalo used to publish a series called “What It Means to Be American,” in conjunction with the Smithsonian. So, I thought it might be fun to ask you: What does it mean to be American?

That is a big question.

I’ll start by saying that Indigenous people who are within the borders of this country are not necessarily in this nation by choice. We have conceded to being American, because these are our homelands and we want to remain in them, and the country has built itself around us. I think we’re put in a position of having to resolve that. It shouldn’t have been our responsibility to have to do that, but I find that we’re asked to quite often.

For myself, I want to look at that responsibility and think about what that means as a steward of the land of the United States itself, both ecologically and as a citizen who shares this land with other people. That’s something that everyone should be conscious of, recognizing ourselves within this place. The land will outlast the nation.

I think we also should consider this border that has been made that we’ve decided, or been forced, to live inside of. How can we blur that? How can we recognize ourselves as citizens within that fence, but also eliminate or blur it? How can we be welcoming? Our questions and efforts of understanding can begin this resolution.

Send A Letter To the Editors