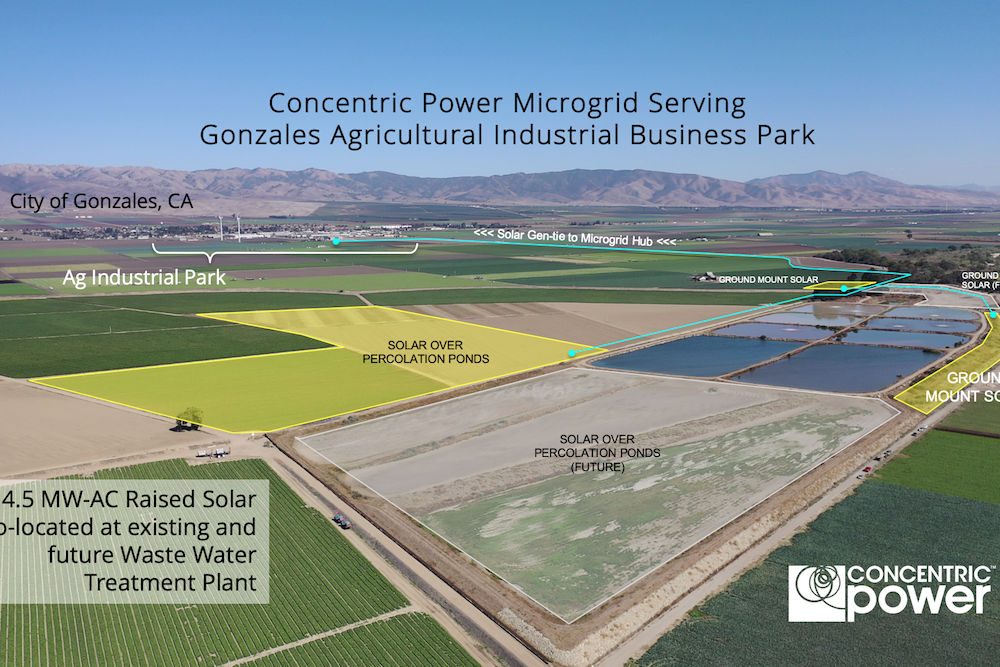

“Gonzales is building its own electricity island among the vegetable fields of the Central Coast,” writes Mathews. Courtesy of Concentric Power.

If California is lucky, our energy future could look like a small town in the rural Salinas Valley.

Longtime readers of this column will not be surprised to learn that the town in question is Gonzales, the California municipal version of the Little Engine That Could. Its small, working-class population of just 9,000, many of them farmworkers, has ingeniously solved tricky local government problems, from universal broadband to health care access, and from economic planning to child development.

Now Gonzales is tackling one of our state’s most stubborn challenges: how to develop local sources of cleaner, cheaper, and more reliable power as our state’s aging energy grid falters.

Tiny Gonzales’s solution? Creating the largest multi-customer microgrid in California. In essence, Gonzales is building its own electricity island among the vegetable fields of the Central Coast to guarantee uninterrupted power, from mostly renewable sources, for the agricultural and industrial businesses that provide the tax base to support its ambitious local programs.

The idea of microgrids—local power grids that can be separate or connected to the larger grid—is not new. In California, they are seen as tools to make electricity service more resilient and to better integrate renewable energy sources, like solar and wind, with the power grid. But efforts to establish microgrids face complex obstacles, from scarce financing, to regulatory barriers that prevent utility customers from sharing power across different grids, to opposition from established utilities.

What distinguishes Gonzales is how the town is bringing together different entities—a savvy start-up applying advanced technology and financing power to microgrids, big energy customers in agriculture and food processing, a new municipal energy authority, and a method for selling power capacity back into the state grid—to surmount those obstacles.

The effort is actually bigger than the town. The $70 million microgrid is the most expensive public works project in the city’s history, dwarfing a $5 million revamping of its Alta Street thoroughfare. But if the microgrid succeeds—it’s scheduled to start producing power next year—Gonzales could provide a model for other California communities, especially those in rural or outlying areas poorly served by the existing grid.

“People want to see if we can pull it off,” says Rene Mendez, Gonzales’s longtime city manager. “We don’t agree with the idea that just because you’re small, you can’t do something like this.”

The problems that drove Gonzales to build a microgrid are familiar across California. The poor reliability of our current grid poses serious problems for companies that depend on steady power sources to operate advanced technology—like the refrigeration and processing machines of the food producers in the Gonzales Agricultural Industrial Park.

PG&E, the investor-owned utility servicing Gonzales and much of Northern and Central California, is so far behind in maintaining the existing grid that many communities, especially in remote places, can’t get the upgrades to the equipment needed to reliably deliver additional power. It could take up to three years for PG&E to update the local energy infrastructure to offer service to any new agricultural-industrial facilities that might move to town.

And PG&E’s use of regional power shutoffs to prevent fires has made finding local power sources that won’t shut down even more urgent. During one 2019 shutoff, Gonzales lost power for two days, resulting in multimillion dollar losses for local employers. This month, a PG&E lawyer said that these intentional outages will continue indefinitely.

Officials spent a decade trying in vain to convince PG&E to upgrade its infrastructure around Gonzales before the city started working on a 2017 plan to produce local electricity with ZeroCity, a Monterey-area company that works with municipalities on energy resiliency, and OurEnergy, a Santa Cruz technical and engineering consultancy. Recognizing that its existing municipal utility couldn’t afford to finance a microgrid by itself, in 2018 Gonzales formed a municipal energy authority that could enlist private financing and overcome some regulatory blocks.

Last fall, Gonzales agreed to work with Salinas-based microgrid developer Concentric Power to design, build, own, operate, and maintain the new microgrid. Concentric will also fund most of the project’s $70 million price tag, earning back its money over 30 years by selling power on a wholesale basis to the city’s new utility. The new Gonzales Electric Authority will contribute about $10 million, and take ownership of the distribution assets. The municipal utility will sell the power—at retail rates lower than PG&E’s.

About 80 percent of the power will come from renewables and about 20 percent from natural gas (which could eventually come from a renewable gas facility the city is also pursuing). The microgrid includes a substation that will allow the sale of excess capacity into the state system, or to Central Coast Community Energy, which serves residential customers in Gonzales.

Effectively, Gonzales is betting that its new microgrid won’t just keep existing food processors in town, but also will make it easier to attract other companies, strengthening the tax base that supports its civic innovation. Additionally, the microgrid should supplement the two giant wind turbines that tower above Gonzales, local landmarks that already serve local food processors. A third turbine might be in the offing.

“This is a community scale microgrid business model that hasn’t existed in the past,” says Salinas native Brian Curtis, founder and CEO of Concentric Power, which is already working on microgrid projects in the Central Valley and elsewhere in the Central Coast. “It’s going to be a watershed project for the state.”

Should the Gonzales microgrid launch and successfully serve multiple customers, it will be a powerful example of local power, especially for rural communities trying to protect or grow industry. Most microgrids serve a single customer or landowner, or are owned by utilities themselves. (In addition to Gonzales, microgrid believers also point to the Redwood Coast Airport microgrid in Humboldt County as a potential model for more powerful, multi-customer microgrids.)

In recent years, California has funded microgrid pilots—from the Blue Lake Rancheria tribal land in the far north to Borrego Springs in northern San Diego County—but it has struggled with the complicated task of creating a regulatory structure that would incentivize localities to produce more microgrids. One especially difficult issue is how to create a system of “microgrid tariffs” to govern how costs and benefits of different grids are shared.

By building its own microgrid, Gonzales is refusing to wait for the rest of California to get its act together. In so doing, one of our state’s smallest towns is, once again, setting a very big example.

Send A Letter To the Editors