Illustration by Be Boggs.

It felt like 2021 was a year of firsts—the first rollout of new vaccine technology; the first insurrection in Washington, D.C.; the first female U.S. vice president; and the first time many of us returned to public life after many months at home. But if we learned anything from the approximately 200 essays we published at Zócalo over these past 12 months, it’s that almost everything has a precedent, for better and for worse.

From a world leader retreating from an unwinnable foreign war (Emperor Hadrian, circa 117 A.D.) to the false promise of automation in the workplace (1950s America), the stories we published provided key context that headline news and hot takes missed. Our favorite essays of the year covered a great deal of territory, from climate change in California and a tragedy in Lebanon to the work of immoral artists and the literature of dentistry. But what we think they all have in common is that, in one way or another, they help us see the world and our place in it anew.

Here are the dozen essays (well, OK, 11 essays and one collection!) that Zócalo’s staff chose to highlight as 2021 comes to a close:

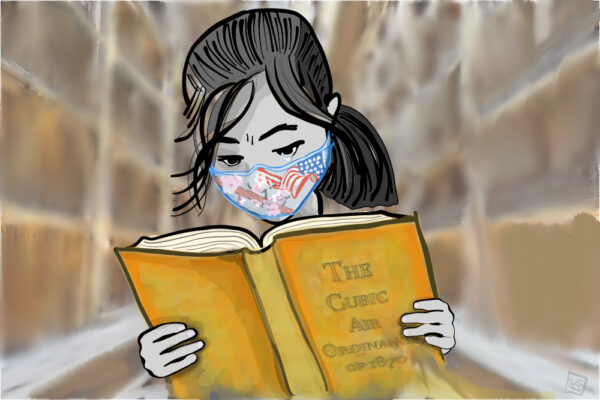

America’s Anti-Chinese Bigotry Has a Very Old Stench

Illustration by Be Boggs.

Almost exactly a year after the first cases of COVID-19 were reported in the U.S., The Smell of Risk author Hsuan L. Hsu explored how American scientists, doctors, and public health officials, as well as historians and novelists, stigmatized “Chinese air” beginning in the 19th century. Hsu demonstrates how these racist, damaging olfactory narratives originated to target the earliest Chinese immigrants to the U.S.—and why it’s no surprise that they remain pervasive today.

Look Away

In 1978, Adam Smyer’s junior high chorus performed “Dixie” at the annual school pageant. Of the couple of hundred people in attendance, “only my mother complained,” recalled the Knucklehead author and attorney. Drawing a parallel to the January 6 attack on the Capitol, Smyer meditates on why it’s not the Nazis, but rather the “not-sees” who may be our biggest existential threat.

The 20th-Century Rise of the Confederate Soybean

Why did the varieties of soybeans grown in the American South suddenly acquire the names of Confederate generals nearly 100 years after the Civil War’s end? This story, from University of Pennsylvania historian and Magic Bean author Matthew Roth, reveals how the USDA spent decades catering to white farmers, which resulted in a more unequal agricultural landscape that persists today.

The Fires California Grieves—And Needs

It may be counterintuitive, but the hugely damaging California wildfires of the past few years prove that California needs more fire. Lenya Quinn-Davidson, a fire advisor in Northern California, reflects on the lessons the fires Native Californians set before cultural burning was criminalized can teach us about fighting today’s megafires, and why every flame holds a story of loss and renewal.

The author’s favorite hometown swimming hole, on the South Fork Trinity River in Forest Glen, California, after last year’s devastating August Complex fire. Courtesy of Lenya Quinn-Davidson.

Where I Go: The Poet Sits in the Dentist’s Chair

“Did you know there’s a rich and under-loved canon of periodontic literature?” asks poet and Wabash College English professor Derek Mong. In this entry from our “Where I Go” series, Mong investigates why he transforms his trips to the dentist’s chair into lectures on books and poetry about teeth—from Edgar Allen Poe and Elizabeth Bishop to Zadie Smith and Valeria Luiselli.

Where I Go: My Small, Queer Corner of the Internet

When he moved from Venezuela to Madrid in 2019, journalist José González Vargas thought he might be able to find the LGBTQ+ community that had eluded him. He did, but not at the bars and bookstores he expected. Rather, once the world locked down, the online platform Discord offered him a space where labels didn’t matter and he could just be himself.

The United States Didn’t Really Begin Until 1848

Gold miners in El Dorado, California, circa 1848. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Forget the hackneyed debate between the New York Times’ 1619 Project and the Trump administration’s 1776 report on when American history begins. “Much like a party that only truly starts when the coolest kid saunters in, today’s United States—antically ambitious, deliriously diverse, violently war-mongering, maniacally money-grubbing, and kaleidoscopically cruel—did not really get rolling until California arrived in 1848,” argues Connecting California columnist Joe Mathews.

Lebanon’s Other Explosion

In August 2020, the world’s attention turned to Lebanon in the wake of the horrific Beirut port explosion. Almost a year later, Beirut-based editor Abby Sewell found herself covering another deadly explosion; this time, the world didn’t pay attention, leaving Sewell wondering what it means to try to tell stories that make a difference when you’re writing for an indifferent audience.

After 150 Years, Is L.A. Ready to Remember the Chinese Massacre?

For most of his life, former L.A. City Council member Michael Woo had never heard of the largest massacre of Chinese in California history, which took place on October 24, 1871. In the first essay of Zócalo’s new Mellon Foundation-supported inquiry, “How Should Societies Remember Their Sins?,” Woo asked why this chapter of history wasn’t widely spoken about, and how a public memorial might help the city finally start to reckon with its racist past.

Can We Still Bump n’ Grind to R. Kelly?

Wellesley College philosopher and Drawing the Line author Erich Hatala Matthes suggests an alternative to “cancel culture”: engaging with the work of immoral artists as a way of clarifying our emotions. “The artwork,” writes Matthes, “provides a lens for reflecting on our feelings, and perhaps the promise of sorting them out.”

What Can We Learn From the Failings of William Mulholland?

“When I read about the crimes of history, I rail against the wrongness of the thinking, the backwards, shortsighted cruelty,” writes author Kendra Atleework, who lives and writes in the part of California William Mulholland drained dry. Her meditation on Mulholland’s crimes exonerates nobody: “I, too, exist within the sticky sap of an era. The things I hold to be self-evident and undeniable may, in time, be proven false and denied.”

How Should Societies Remember Their Sins?

In January 2021, on the same day as President Biden’s inauguration, Zócalo began publishing a group of essays about why, from Japan and Germany to the American South, societies around the world struggle to acknowledge the crimes they committed—and persist in repeating them all over again. We published too many wonderful pieces to single any out, and we’re looking forward to turning to this question throughout 2022 and into 2023, now with the support of The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Illustration by Mary Kirkpatrick.

Send A Letter To the Editors